Rich countries run the world economy. The G7 – the US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Japan and Canada – directly manage all major international bodies or greatly influence how these work. In the process, they set the terms for international trade and investment. Any country that disobeys their US-led ‘rules-based order’ is faced with sanctions, economic isolation and military threats. But the past six months have seen accelerating moves to build a framework outside this web of domination. This article assesses those building blocks for a new world economy.

---

1. Introduction: BRICS momentum

The BRICS acronym represents Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. They are not in the rich G7, but account for some 40% of the world’s population compared to the G7’s 10%. Each has a different political stance, but they have a common interest in cooperating for national economic development. A BRIC country group was set up in 2006; South Africa joined the original four in 2011. Subsequent years saw little progress in cooperation. Instead, it was China that pressed ahead, through its Belt and Road Initiative, an infrastructure, transport, trading and investment project that came to include more than 140 countries.

One reason for the BRICS’ previous lack of progress was the elections of Prime Minister Modi in India and President Bolsonaro in Brazil that helped the US fuel suspicion in those countries about China. Another was Russia’s earlier stance, when it saw more immediate benefits from trying to expand trade and investment links with the countries of western Europe. Yet, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and multiple sanctions against Russia from the Western powers, the BRICS project has sprung back into life! Several other countries now line up to join it.

Why is this? Why would a country risk any dealings with Russia and face the disapproval of, even sanctions from, the US and Europe? It looks like an odd thing to do only if one follows the Western mainstream media. Contrary to Western propaganda about universal condemnation by the ‘international community’, sanctions against Russia have not been followed by countries with 85% of the world’s population![1] The following chart gives a geographical picture of the sanctioners: none in Africa, none in Latin America (apart from a few small islands) and very few in Asia. Those decisions might rest on different reasons, but it is undeniable that many countries have a less than happy memory of Western escapades on their territories. More than a few recognise the support that Russia has given them in the past. That is quite apart from any knowledge they have – likely more than is common in Western societies – of the provocations that led to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[2]

The So-Called ‘International Community’ Sanctioning Russia

The lack of reality in the West’s notion of an ‘international community’ united against Russia was also shown in July this year, when Russia’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov received a warm reception from his Arab League counterparts in Egypt. He later met representatives of the African Union in Ethiopia and went on a tour of several other countries.[3]

---

This review starts by examining some of the key resources in the BRICS countries, together with Argentina, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, other potential BRICS members. These additional candidates underline how the BRICS grouping is not an ideological bloc, but a pragmatic alliance. They have certainly not decided to end all relations with the Western powers, but they have seen the limitations these have for their own development – most evidently in the case of Russia, and to a lesser extent also China – given the sanctions regimes imposed by the West. Furthermore, the BRICS are increasingly allied with other political-economic groups outside the Western sphere of influence, as will be detailed.

BRICS and other allied countries are not the only, and may not even be the main ones, that produce key resources. A feature of the world economy, and a progressive one, is that countries trade their resources and provide what others may need but do not have. But this trade is greatly impacted by Western sanctions, especially from the US, and – often in line with US policy – also the UK and the European Union countries. So it also critical where things are produced, and what economic or political ties exist.

After noting some basic products, food and energy, the review covers a wide range of other metals and materials, highlighting the ones that are mainly produced in the expanding BRICS group. There follows a brief assessment of technology, the growing transport, political and trade links, and lastly an overview of the financial relationships being established between some key groups of non-Western countries.

If these countries cooperate, then as a group they can produce more or less anything they need. They do not have to rely on being permitted to operate by the Western powers and can be in a position to conduct business outside the usual spheres of bullying, via sanctions or other aspects of the dominant world order.

---

2. Food

Countries aim to produce food for their citizens, if they can, so China and India with big populations are also big producers. Otherwise countries must depend upon what may be an insecure supply from others. Climate conditions and landscape have a big effect on what can actually be produced, and the volume potentially exported, which also affects the type of food a population normally eats. Next is a snapshot of the production of wheat, corn and rice, together with the populations of the selected countries. These are the most important staple food items for majority of people on the planet, although people do ‘not live by bread alone’.[4]

(Updated for BRICS-11, if Argentina actually joins!)3. Energy

A similar picture can be given for energy output. The expanded BRICS group produces plenty of coal (mainly China), but a bit less oil and gas as a share of the world total, while the US stands out as a major energy producer. Note that China has greatly expanded, and is very big, in solar, wind and hydroelectric ‘green’ energy, not just in fossil fuels. However, such energy sources, though increasing rapidly, are only a minority of China’s total energy supply, and this is the same for almost all other countries.

(Updated for BRICS-11, if Argentina actually joins!)

Concerns about climate change mean that coal, oil and gas are looked upon in a different light these days! However, they remain by far the key source of energy for most countries: 82% of the world’s total energy consumption in 2021. Nuclear energy accounted for only 4% of world consumption; hydroelectricity and renewable energy sources made up about 7% each. Renewables are growing relatively quickly, however, as new capacity is installed for solar, wind and hydroelectric power generation. China’s prominence in the main areas of ‘green’ energy is shown in the following images.[5]

For solar energy, China’s share of the global total is 36%:

For wind energy, it is 40%:

For hydroelectricity it is 30%:

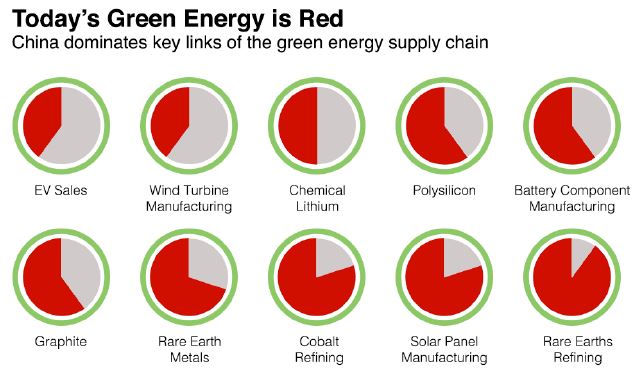

In addition to this ‘green energy’ capacity, China is also very prominent in the global supply chain for these products, as the next chart shows:[6]

---

4. Metals, minerals, rare earths

A country might have very big reserves of a raw material. If it has, then can it process the material, or produce what is needed for an end-product, let alone being able to make the end-product itself? But if one notes only the refining or end-product manufacturing, where do the basic material inputs come from? Can the country producing at any stage get access to the technology or machinery required? The following review covers selected raw materials for which there are data for a wide range of countries, and it notes the relevant stages of production.

There is a vast range of metals, minerals and rare earths needed for making all kinds of items. Although in some cases it might be possible to substitute one element for another, often the existing technologies do not allow it. Furthermore, almost all products are made with many inputs. For example, a mobile phone usually contains more than 50 elements – from copper, to lithium, nickel and zinc, to neodymium, palladium, phosphorus and thulium.

Here I focus on where the BRICS countries account for a large share of the world’s resources. The different stages through which a raw material goes, from extraction to the refining and manufacturing before it becomes (part of) a final product would need to be taken into account to get the full picture. There are also multiple uses for the products and by-products of different stages of the production process. Furthermore, metals are often used in combination with other metals or chemical elements (alloys, compounds, coatings) to improve their strength, resistance to corrosion, etc. This review sidesteps such a complex web of links and aims only to give an outline. Items are considered in alphabetical order, with a note of their key uses.[7]

Bauxite, Alumina, Aluminium: Bauxite is the ore that is mined, processed into alumina and then refined into aluminium metal by smelting. Key uses of aluminium are for drinks cans, aircraft and other transport vehicles, in the construction industry and in many other areas, encouraged by its good strength and low density.

Around 32% of world bauxite production comes from African countries, 28% from Australia and 22% from China. For alumina, China produced 53% in 2021, Australia 15%, Brazil 8% and India 5%. China was similarly prominent in aluminium smelter production, with 57% of the world total. India and Russia had just under 6% each. So the BRICS countries have an important share of these resources. Many countries have aluminium smelters, but production is energy-intensive, and access to relatively cheap energy is a key part of the economics here.

Cement is an important material for the construction industry and 2021 saw 4,400 million tonnes produced worldwide. China accounted for 57% of that, reflecting its massive construction programmes. India, next in line, produced nearly 8%.

Copper is essential for electrical wiring and motors, and is widely used in plumbing and industrial machinery. Chile is the world’s biggest mine producer of copper, but China had the biggest share of world refinery production in 2021, at 38%, ten times that of the US. Russia’s refinery output was just below the latter’s.

Australia is by far the leading mine producer of iron ore, used to make steel, with 35% of the world total. The five BRICS countries as a group nevertheless have a 45% share between them, with China and Brazil the biggest of the five. In terms of steel output, China accounted for nearly ten times more than any other country in 2021, producing for 58% of the world total. Other BRICS countries had a further 12%.

Lithium is a key element, especially for the production of lithium-ion batteries used in mobile phones, other devices, and in electric vehicles. It is the least dense of all the metals and can give batteries a high power-to-weight ratio. One survey cites Australia as having the biggest lithium mine production in 2021 with 55,400 tonnes out of a world total of 106,000. Chile was next with 26,000 tonnes, China third with 14,000 and Argentina fourth at 6,000.[8]

Palladium and platinum can often be substituted for one another in many industrial uses, such as catalytic converters in auto engines and these metals are also used to remove toxic emissions from vehicle exhaust fumes. South Africa has the largest mine production of each metal; 40% of world output of palladium and 72% of platinum. Russia is the second biggest producer, with 37% and 11%, respectively.

Rare earths are a group of 17 soft, heavy metals. The ‘rare’ term refers to how they are not often found in economically exploitable deposits. These elements are used in batteries, magnets, lasers, lenses and X-ray machines, among other things, and have been increasingly used with the growth of modern technologies. Much to the chagrin of the Western powers, China accounts for the bulk of world mine production of rare earths, with 60% of the total. Russia and India each have another 1%. The US has 15% of total rare earth mine production; Australia 8%.

Titanium is often used in alloys to produce strong, corrosion-resistant, lightweight materials for jet engines, industrial processes and many military uses. China produces about half the world supply of titanium sponge, and Russia about 10%. Russia has been a major supplier of titanium to Europe’s aerospace industry.

Tungsten has a high melting point, high density and hardness that can make it a useful alloy material, especially for industrial and military uses. In 2021, China accounted for 84% of world mine production of tungsten, Russia another 3%.

If a group of countries has a good supply of food, energy, metals and raw materials, that is not much good if there is little ability to transform these into the relevant products, or to transport these products between the different countries. So the next two sections look briefly at technology and transport links.

---

5. Technology

A longstanding view of mainstream Western economics is that the rich countries are rich because they have better technology and higher productivity, and so higher living standards, than poor countries. Of course, this belief overlooks how much of the world’s manufacturing industry – including all the latest technology – has migrated to the ‘cheap labour’ countries in recent decades. While many of the main advances in production and communications technology have originated in the rich Western powers, they have often used these inventions/innovations as ‘intellectual property’ that can be licensed to the countries that actually do the producing. For example, in 2021, the US had export revenues of $56.4bn for the licences to use the outcomes of its research and development, and another $36.6bn for licences to reproduce or distribute its computer software.

These days, the rich countries dominate production only in a few areas that can be more easily monopolised, for example in specialist engineering and medical equipment or in pharmaceuticals. So, for example, they will produce specialist steel output, not the mass-produced items. Yet, this strategy tends to fail when other countries also build up their own research and technology! The case of semiconductor production is illustrative, showing that the US and Japan are important in the first parts of the supply chain, but Taiwan and South Korea are critical, and China also has a key position.

Much of the world supply of the inputs for semiconductors comes from companies based in the US, with Japan and the Netherlands having an important role too. Other countries, such as South Korea and Taiwan, successfully developed their own industries. The latter were helped by being favoured by Western imperialism as safe, controlled outposts, and they were able to overcome what otherwise could have been significant trade barriers.

South Korea and Taiwan stand out in semiconductor device manufacturing, foundries and design. But China’s Huawei and SMIC also have an entry in the latter two areas. This is due to China’s huge investments in modern technology, giving encouragement to local companies. China still has to catch up with the leading global companies in all stages, but that outcome is a likely prospect in coming years – ironically, spurred by US sanctions aiming to hold back China and its key companies, particularly Huawei.[9]

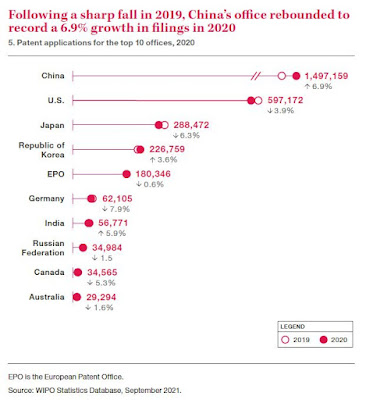

One indication of the continued prominence of China’s R&D comes from the record of patent applications compiled by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Although the number of patents need not tally with the volume of significant inventions or innovations, they will give an idea of what is going on. In 2020, patent applications from China were by far the largest in the world, 2.5 times more than from the US in second place, and five times more than from Japan in third place. The top three areas for Chinese patents were in computer technology, measurement, and electrical machinery, apparatus and energy. Other leading patent-applying countries were the US, Japan, South Korea and Germany, each with a different area of specialisation. India and Russia were also in the top 10.

Filing for Patents in 2020, Top 10 Countries

For Russia, the longstanding hostility from the West, plus Western sanctions, have led it to focus on military and space technology as a means of defence, rather than on areas that might pay off in producing industrial and consumer goods. So Russia has the world’s first hypersonic missiles and, arguably, a lot of battlefield equipment that is more advanced and with a greater capacity than that produced by NATO countries. Following Gazprom’s trouble with getting Germany’s Siemens to repair and replace turbines for the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline, one report noted that Iran was able to provide suitable alternative turbines.[10]

---

6. Economic developments: BRI

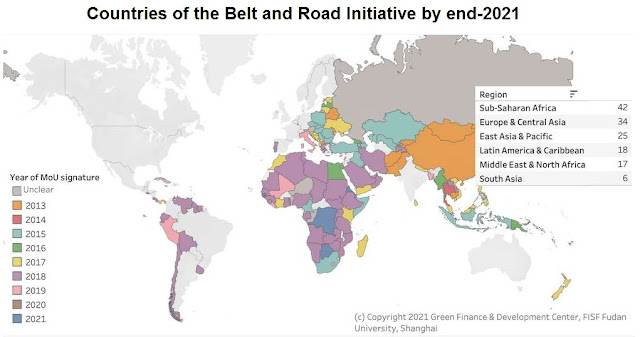

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was launched in 2013. It is hugely ambitious and aims to develop ports, shipping lanes, roads, railways, bridges and other infrastructure, including power stations and high voltage electricity grids. The project is promoted and largely funded by China, and its potential attracted 146 countries by the end of 2021. Rather than being confined to the Eurasian landmass, there are BRI member countries in southern Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America.

The next chart gives the BRI’s geographical reach, and the year when a ‘Memorandum of Understanding’ was signed by the countries concerned. There appears to be no formal signing of an MoU on Russia’s part, so it is not included in this particular chart. But there has evidently been much Russian economic cooperation with China, so Russia is included in the BRI in a later image.

In a pathetic attempt to counter China’s BRI in June this year, the US proposed a ‘Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment’ along with other G7 members. The supposed $600bn plan was full of rhetoric and promises, but with few specifics and even less cash actually being committed. The implicit fundamental condition for countries to receive any funds from it was to sign up to the Western ‘rules-based order’![11] Real life BRI-related infrastructure projects weigh far more heavily in the minds of governments assessing development possibilities than such rhetorical games. Here are some recent BRI projects:

- China has organised the building of dams to generate hydroelectric power in Laos. These can also export electricity, and can be used for expanding the railway system, such as the China-Laos Railway, opened in December 2021.

- Building of Indonesia’s first high speed rail link between Jakarta and Bandung is near completion. Bullet trains will be delivered in coming months, for the line to open in mid-2023.

- The road and rail Padma Bridge project was opened in June 2022, and connects 21 areas in southern Bangladesh.

- Many projects financed and built with considerable help from China have been completed in African countries. In January 2022, China announced support for the massive extension of Kenya’s Mombasa-Nairobi railway to Uganda, South Sudan, and the DR Congo. The railway will be linked to the Addis Ababa line, and then to Djibouti and Eritrea.[12]

- In February 2022, Argentina and China signed a deal whereby China will build an $8bn nuclear power plant, Atucha III. This will be the biggest of Argentina’s nuclear plants, providing an electrical output of 1,200 MW.

News coverage of the BRI investments in the Western media always focuses on the supposedly exorbitant costs, the reported bribery of corrupt politicians, and how they burden the receiving economy with ‘unsustainable debt’. And yet, the schemes almost always succeed in boosting local economic development. That media coverage makes no attempt to measure the Chinese investments against the Western alternatives, which are often no projects at all. Further, such reports ignore the Western methods of exerting political and financial pressure to influence policy in developing countries – via the IMF, the World Bank, or more directly through bullying and bribery.

The Western complaints of corruption, debt, etc, are usually just sour grapes, and are hardly specific to China’s involvement. Such problems are often linked to widespread corruption in the ruling government elites, as in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota International Port project. Sri Lanka’s debt problems have little or nothing to do with China: around 90% of Sri Lanka’s outstanding debt is to Western banks, and is usually at much higher interest rates than those on China’s loans.[13]

Finally, on the BRI, the argument here is not that only China is financing economic development, or that the countries concerned do not make efforts themselves. The point is that China has clearly stood out as assisting such developments with large scale finance on attractive terms – at least better than otherwise available – and an ability to bring many projects to fruition. At a minimum, by its potential involvement in such projects, China also creates an alternative to what might be on offer from Western banks and corporations, and this gives developing countries more bargaining power to get a better deal.

---

7. Transport links: BRI, INSTC

If a group of cooperating countries has most of the products it needs and the technology with which to make them, then what about transport links between the countries concerned? Countries bordering each other, or in close proximity, usually have road, rail or sea connections, as well as by air. That these exist is nothing exceptional, and may not indicate any formal alliance or significant economic ties. Yet there are interesting, and growing, connections between many of the BRICS members and these are part of definite projects over the past decade, not links that have developed haphazardly over the past century and more. These projects also encompass many countries outside the formal BRICS grouping, and they form the skeleton around which a ‘non-Western’ economic body can be built, especially, but not only, in the Eurasian region.

The following network map shows a part of China’s BRI network, discussed in the previous section. It does not show any extension into Latin America, but it does highlight some of the main connections into Eurasia, Europe and East Africa. The BRI’s spread into Western Europe has in recent years been very active – for example, the rail freight line from Western China into Duisburg, Germany, the world’s largest inland port with connections across Europe. However, the European connections could well be brought into question if the EU countries continue their disastrous foreign policy tie up with a US that is getting more aggressively anti-China!

China’s Belt & Road Initiative Network [14]

There is also a separate, but complementary, transport network, the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC) promoted by Russia. The founding members of the INSTC in September 2000 were Russia, India and Iran. The project now includes a number of other Eurasian countries, and it has invested in many road, rail and sea transport links, shown in the image below.

Compared to the BRI, the INSTC has a more definite Eurasian bias, and links to other regional initiatives. Great efforts have been made to streamline and reduce costs. Such moves entail sorting out customs borders, the taxation on trade, freight costs and connecting up more efficiently the potential switches from road, to rail, to ship along the many routes – for example around or over the Caspian Sea, or from north-west Russia through Iran and then via the Arabian Sea to Mumbai, India. The potential for this transport network to have a positive impact on economic development in the countries involved should be clear.

By including Iran, like the BRI, the INSTC network indicates how far removed it is from the sanctions regimes of the Western powers! Most of the transport routes do not traverse sea lanes at risk of Western control, so this also offers an extra measure for their economic security.

The INSTC and the Eurasian Transport Framework [15]

---

8. Political links: SCO, EAEU, CSTO

There are many conflicting aspects of the political alliances between countries in these projects. For example, India is a member of the US-led ‘Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’, usually referred to as the Quad, a strategic security format composed of Australia, India, Japan and the US that is aimed at China. Similarly, Turkey, that wants to join the BRICS group, is also a NATO member, the US-led organisation that militarily backs Ukraine against Russia. Many others could be noted, not least Saudi Arabia’s opposition to Iran,[16] and they would not seem to bode well for expanding BRICS, let alone for the other political groupings. Yet, the momentum behind the recent changes makes one draw a different conclusion.

That momentum is based on an effort by these countries to generate economic development. In the past, that was possible for some countries seen by major Western powers as key for sustaining their hold on the world economy. For example, consider the ‘Asian tigers’ of the 1960s to the 1980s – Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. The first two were favoured financial and trading posts of British imperialism, the second two were given political-economic concessions by US imperialism that helped boost their national economies. In the latter case, those countries were also valued by the US as counter weights versus North Korea and China.

In more recent years, a number of other economies, particularly in Asia, have also grown. But often this has been in a one-sided fashion, where they are very dependent, low-wage sites for the offshore production of cheap goods for Western consumers. The limitations of that mode of ‘development’ are now more clear for many countries, and they want something better. China’s model looks a much more attractive option! It is more attractive still because it is offered with no interference in a country’s internal politics. It is also part of a large group of countries establishing wider cooperation outside the Western-prescribed channels.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is a more definitive group of countries than the BRICS, or those in the China-led BRI. The SCO was established in 2001 from an earlier 1996 group that had focused on sorting out border tensions between them. India and Pakistan became full members in June 2017, bringing the current total of eight countries with this status. The SCO now has broad, clearly stated political and economic aims:[17]

- strengthening mutual trust and neighbourliness among the member states;

- promoting their effective cooperation in politics, trade, the economy, research, technology and culture, as well as in education, energy, transport, tourism, environmental protection, and other areas;

- making joint efforts to maintain and ensure peace, security and stability in the region;

- moving towards the establishment of a democratic, fair and rational new international political and economic order.

The evidence shows that one cannot dismiss these objectives as just abstract, empty homilies. They want to get comprehensive areas of cooperation between the member countries, and the objective is to build a new international system.

Reports of SCO membership are often not clear, partly because there are graduated steps before becoming a full member, first as a Dialogue Partner, then as an Observer, then as a Member. The next chart is based on the latest information on the SCO’s website, and also includes items from recent news reports that Syria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates want to sign up.[18] If that happens, it is a major blow to US and UK influence in the Gulf and Middle East region. Iran is also expected to move to become a full member in September 2023. Note that a US application to join the SCO as an observer was rejected in 2005, and it is not likely to be repeated.[19]

Shanghai Cooperation

Organisation: Members & Applicants

There are other political groups in the Eurasian region, including the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO). Membership of each consists of Russia, plus five or six ex-Soviet states and some other observers. These groups do not have much pulling power for countries outside the former Soviet bloc, and the economic and political ties between member countries are also somewhat fragile. One member of the EAEU, Kakazhstan, was concerned that it would have to follow Western sanctions against Russia or risk becoming sanctioned itself and be cut off from Western markets and inward investment.[20] Three members of the CSTO also took part in a US-led military exercise in early August this year in Dushanbe, Tajikistan![21] Nevertheless, the EAEU and CSTO have overlapping memberships, and many shared objectives, with the SCO and the BRI, and with the INSTC transport network noted before.

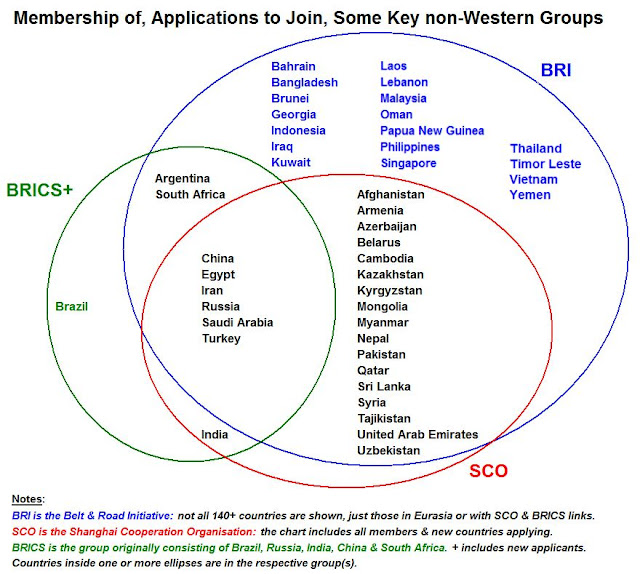

This can be a confusing set of acronyms for readers who have not followed these developments. To make the country links clearer, focusing just on the BRICS countries, the BRI and the SCO, the next chart shows how far the memberships overlap for 45 countries. (The chart does not include all 146 BRI members, and misses out many in Latin America and Africa.)

---

9. Sanctions, trade, finance, US dollar, alternatives

Recently, non-Western countries have made make their plans for closer, direct economic cooperation more of a reality, not a vague hope for the future. Much of the explicit political momentum behind this has come from Russia, but China has also been heavily involved, given its extensive economic ties. Russia had already responded to previous Western sanctions and began to develop ways of not relying upon business operations that could easily be closed off by the US and its allies. Following the new, extraordinarily wide range of sanctions imposed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, other countries have also woken up to seek alternatives.

There are two main ways the West imposes sanctions,[22] and different ways these can be avoided or minimised. But that is not as simple to do as it might first appear, and all the alternatives imply the need to set up a system outside the existing one that dominates the world economy.

Mechanisms of Western sanctions

One sanctions method is on international trade, where some, even all, exports to or imports from a targeted country are stopped. While the target of US sanctions might find other suppliers or other export markets than the US, the problem is that US allies will often follow suit – or else they might themselves be fined or threatened. As the case of Russia has shown, the sanctions can also be extended into things like air, sea, rail and road transport, and insurance services, not just on goods. What this has spelled out is that relying on the continued workings of ‘normal’ business with the Western powers puts a country at risk! China has found the same to be true, although so far on a smaller scale and in a more limited scope, principally related to its trade with the US and not so much (yet) with Europe.[23] Even if sanctions are circumvented, as often happens, that can mean extra costs for doing international trade.

A second method is for the US/Western countries to try and ban financial transactions with a target country. This can be done, or those transaction made very difficult, by preventing that country’s companies and banks from having access to the SWIFT system, or to be able to complete deals involving the US dollar (or euro, etc). It might be thought that an easy way out would be simply not to use SWIFT, or not to use the dollar, but that is not so easy in practice.

The SWIFT system is a bank messaging system for payments, not the payments themselves. It is the standard system used to pass on instructions for most international payments.[24] The operation is based in Belgium, although the US National Security Agency monitors the messages going through SWIFT! Alternative messaging systems do exist, including one set up by Russia, but these have so far been used by few other countries, and they need banks to adopt another set of identification codes and communication procedures.

Similarly, a country could decide not to use the US dollar in its external trade, but that would stand against the overwhelming use of that currency in global transactions. Most of the goods and services traded internationally are priced in dollars, from commodities like oil, metals and agricultural products, to aerospace, pharmaceuticals and weapons, let alone the bulk of financial securities. That is why the US dollar is involved in 88% of all foreign exchange transactions. [25]

The problem of using the US dollar to transact is that all flows of funds between accounts – no matter where the buyers/sellers are based – must pass through the US banking system. This is not evident at first. After all, if a German bank wanted to transfer dollars to a French bank, why would they need to go via the US? Yet that is how the transfer works, via one of their branches, or a correspondent bank with which they have links, actually inside the US banking system. As a result, they can be monitored by the US authorities, which can fine or shut down any bank doing a disallowed transaction on its territory. The US Treasury even has a special department to enforce economic and trade sanctions, appropriately called the Office of Foreign Assets Control![26]

Some ways around them

Yet, ways around this network of US/Western domination are possible. It is then a question of the countries concerned about this having the political will to step outside the established Western systems they use and to make an effort to build something else, or to work in other ways. That political will has been growing in many countries over the past year, as the following examples show:

- Russia has an alternative to SWIFT, called SPFS. At present there are around 52 foreign organisations from 12 countries using the SPFS system, but the numbers should grow.[27] “Russia has offered countries belonging to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to join its financial messaging system (SPFS), the Russian equivalent of SWIFT. Moscow wants to boost the volume of settlements in national currencies, the country’s Economic Development Minister Maxim Reshetnikov said on Tuesday [16 August].”[28]

- India is reported to have agreed to pay for Russian oil with Russian rubles, not US dollars, and Turkey will also pay for some Russian gas supplies with rubles.[29] Russia had already stipulated in March that payments for its gas supplies to Europe had to be settled in rubles. This was to be done by customers paying in euros as in the contract, but also opening a ruble account at Gazprombank which did the FX transaction into rubles. After controversy and misunderstanding, customers for three-quarters of the gas complied.

- India’s central bank has allowed the expanded use of the Indian rupee in trade settlements for imports and exports with Russia and other countries.[30] India was also reported to be paying for Russian coal in non-dollar currencies, including the UAE dirham, Hong Kong dollar and Chinese renminbi, as well as the euro.

- Indonesia and China in 2021 planned to reduce their reliance on the US dollar and to start using their own currencies for bilateral trade and investment.[31] Currency swap arrangements between their respective central banks to assist this trading are already in place.[32]

- In what could become a major break in the usual OPEC oil pricing deals, formerly all in terms of US dollars, Saudi Arabia in March this year was reported to be ready to accept payments in Chinese renminbi for sales to China.[33] This would follow other Saudi moves to diversify its revenues, as well as to signal a closer relationship with a major trading partner.

- After Visa and Mastercard pulled out of Russia earlier in 2022, Russia has expanded the international links for Mir, its domestic electronic payment card system. This was also another way of avoiding the SWIFT system for (smaller scale) international payments, if other countries would accept it. So far over a dozen countries accept the Mir card, mostly those in the former Soviet Union, but also in South Korea, Turkey, India, Vietnam and Cuba.[34] It will also be accepted in Iran and Sri Lanka by the end of 2022. The Mir card is linked to China’s Alibaba online retail service, AliExpress, and to China’s UnionPay system – although this latter link has been limited by sanctions on Russia.

- The BRICS countries are discussing a new international reserve currency, possibly based upon a basket of their own currencies. This will take a long time to work out and implement, but signals another move away from the US dollar as a reserve currency and also the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket currency.[35]

Such examples are many and growing. While still on a very small scale compared to the volume of deals in global trade and finance, they show the potential for a new system to be built. In this process, Russia has done most of the political advocacy, and is most determined to give a robust response to the Western sanctions it has faced. Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister recently said that the US dollar and the euro have become ‘toxic’ and that the Western-made financial system is “unsuitable for the conditions of a multipolar world order and has essentially become an instrument for achieving political goals of one group of countries”.[36]

By comparison, although China has played a big part in building an alternative system, particularly with the BRI, it has been on a much quieter path. China does not wish to upset its relations with Western countries more than necessary so that it may still achieve its development aims. The US provocations around Taiwan may well change that stance, however.

Extracting the entrenched US dollar

One other point of difference between the approaches of Russia and China can be seen in their countries’ foreign investments. Russia, having long suffered from Western sanctions, has very little exposure to the West, except through its large foreign exchange reserves. It made a big effort to reduce the holdings of US dollars in its reserves and instead built up holdings of gold and especially Chinese renminbi securities in the period to end-2021. But it made the mistake of not expecting the EU countries to follow US sanctions as avidly as they did – and even to a more extreme level! – so it also built up its holdings of euro deposits and securities. I would estimate that of the $300bn of Russia’s FX reserve assets seized/frozen/stolen earlier this year, at most ‘only’ about $60-70bn was in US dollars, while up to $210bn was in euros, with the rest in other Western currencies.[37]

China’s holdings of Western investments are far bigger, both in its FX reserves and in other investments. The official figures detailing those held in the US are understated because they do not count the all investment that has come from Chinese companies, for example via tax havens such as the Cayman Islands. Yet they still show a total of $2,046bn for mid-2021 in US equities and bonds, counting both mainland China and Hong Kong.[38] Much of the $1,603bn bond holdings component registered will be for China’s and Hong Kong’s FX reserves.[39] While there has been some fall in these holdings in the past year, there has been no sign yet of any significant move to cut them.

There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, global trading remains very US-dollar dominated and, as a by-product of this, official institutions and private companies hold dollar assets in their balances and reserves. Secondly, the Hong Kong dollar has an exchange rate tied to the US dollar as part of a currency board system, so the central bank authorities need US dollar securities holdings to back this up.[40]

It will take a long time before the US dollar can be expunged from China’s financial markets, and still longer from other Asian markets. Yet the developments noted here indicate that a definite move is under way to diminish the role of Western currencies in the trade and investment relationships between the countries taking part in these non-Western groupings. In any case, for as long as the Western powers do not actually seize Chinese assets, cut China out of SWIFT or stop it from being able to complete transactions in US dollars, etc, then China can continue to use these funds as it wishes.

---

10. Conclusion: World in transition

China has been the principal economic motor behind what has been discussed, although one should not ignore its political initiatives. We can expect the latter to be stepped up as the US gets further into panic mode about its ability to dominate the world system. Russia has been the more explicit political motor, and its ability to have that role is also linked to its valuable economic resources.

A world economy seen through the lens of GDP data and financial power gives a very distorted picture. On the IMF’s latest estimate for 2022, Russia stands below Italy, the smallest of the G7 countries, in terms of its nominal GDP. Russia’s stock exchange, foreign investments, banking system and currency barely register in a tally of global markets. But it did not take long for European countries, and even the US, to suffer from the sanctions they had enthusiastically imposed on Russia! A far worse outcome for them awaits if they decide to go down the same route against China. Producing necessities for people’s living standards is not such a dumb thing to do after all.

That is one lesson from the events of the past months. A longer and harsher lesson already learned by many other countries is that if they are looking for economic development, the Western imperial system offers them nothing. Until recently, there had been little other recourse. But economic and political groups outside the political control of the Western powers are growing. The West will do its best to sabotage these, but they will continue to attract members because they can offer countries a better future.

The ruling Western powers will not give up their ability to dominate and exploit others without fighting back. They have a lot to defend, especially the US which relies upon ‘full spectrum dominance’ – from its influence over major international institutions, to its securing the central role for the US dollar in world trade and finance, to its promotion of militarism and crises in every region of the planet. Although the West European countries – the UK, Germany and France, especially – look like minor players by comparison, they are also important in this network of domination. They fear losing their place in it and so have jumped enthusiastically on the US bandwagon, despite their economies now suffering badly.

Economic and political sanctions on Russia were first aimed at punishing a country that had the means to defend itself from encroachment. They were also a means of trying to force the rest of the world to fall into line, to make clear that nobody can disobey the ‘rules-based order’. That term signals the flouting of any notion of international law and replaces it with whatever the ruling powers see as necessary to sustain the existing order that serves them. Yet, the evidence suggests that many countries are now waking up and will cooperate in building a different framework for the world.

This is all very much a work in progress and it could suffer setbacks. One condition for its success is Russia’s success in Ukraine, the conflict that was promoted by and prolonged by the US and its NATO allies. A defeat for the latter will be a severe political blow to the hegemony of the ‘West’. It will also be a signal for more countries to join the alternative project!

Tony Norfield, 5 September 2022

[1] Western media coverage usually cites the number of UN votes on these issues, but that ignores how each country in the UN has one vote, whether its population is less than 50,000 or over 1 billion. Many sanctioners were tiny population countries, often islands that were either bullied by or under the control of the Western powers.

[2] For some of the background to the Ukraine conflict, I would recommend reading this article by Jacques Baud, a former Swiss intelligence officer: https://www.thepostil.com/the-hidden-truth-about-the-war-in-ukraine/. Other people who have informative material on this question, and know what they are talking about, include (retired) US colonel Douglas Macgregor, Professor John Mearsheimer and Scott Ritter.

[4] It was not possible to give a concise summary of global meat, fish/seafood, vegetable and fruit production.

[5] The following three charts for 2021 are produced from data in BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy, 2022.

[6] Source: Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School, The Great Tech Rivalry: China vs the U.S., December 2021, p34. This report would more consistently be titled ‘The US vs China’!

[7] Data below are taken largely from US Geological Surveys of world resources, with some additional information from other sources indicated. Recycled material is not considered here, but in some cases it might be an important additional resource. Data are for the year 2021 unless otherwise noted.

[8] BP, Statistical Review of World Energy, 2022.

[9] The following chart on the companies involved in the semiconductor supply chain was taken from Chad P Bown, ‘How the United States marched the semiconductor industry into its trade war with China’, Peterson Institute for International Economics, December 2020. Also see my article on the US versus Huawei: https://economicsofimperialism.blogspot.com/2019/04/racism-imperial-anxiety-us-vs-huawei.html. Note that Huawei has also consistently been the top global company measured by patent applications, a sign that the US sanctions have done nothing to dampen China’s R&D. On 25 July 2022, Asiatimes reported that China’s SMIC has been able to produce a 7 nanometre chip, ahead of the US and Europe, although one that may be inferior to those produced in South Korea and Taiwan. See https://asiatimes.com/2022/07/smics-7-nm-chip-process-a-wake-up-call-for-us/

[10] https://en.topcor.ru/27056-turbiny-nemeckogo-koncerna-siemens-v-rossii-mozhet-zamenit-iran.html

[11] The official US statement on this is at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/26/fact-sheet-president-biden-and-g7-leaders-formally-launch-the-partnership-for-global-infrastructure-and-investment/

[12] See this article by Matthew Ehret for further details of projects for economic development in Africa, by both Russia and China: Russia in Africa: Connecting continents with soft power, 1 August 2022, here https://thecradle.co/Article/Analysis/13716

[13] For a surprisingly fair assessment of China’s investments and the dominant influence of local country factors, see the UK’s Royal Institute of International Affairs’ Chatham House paper entitled Debunking the Myth of ‘Debt-trap Diplomacy’ How Recipient Countries Shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative, August 2020. Another debunking is in The Atlantic, 6 February 2021, an article entitled The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ Is a Myth, at https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2021/02/china-debt-trap-diplomacy/617953/

[14] Source: Oziewicz and Bednarz, ‘Challenges and opportunities of the Maritime Silk Road initiative for EU countries’, Scientific Journals of the Maritime University of Szczecin, October 2019.

[15] Source: Eurasian Development Bank, Reports and Working papers, 21/5, https://eabr.org/en/analytics/special-reports/the-international-north-south-transport-corridor-promoting-eurasia-s-intra-and-transcontinental-conn

[16] Interestingly, there are reports of some rapprochement of Saudi Arabia with Iran. If continued, this would be a major political development in the region. https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220722-iran-says-saudi-ready-to-move-reconciliation-talks-to-higher-level

[17] The SCO’s two official languages are Chinese and Russian, but there is also an English language website: http://eng.sectsco.org/about_sco/

[18] The next SCO annual summit that may decide these issues is on 15-16 September 2022, in Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

[19] See this early report on the SCO: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2006/jun/16/shanghaisurprise

[20] Kazakhstan also aimed to attract Western companies exiting Russia after the sanctions were imposed. See https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/kazakhstan-in-talks-with-foreign-companies-planning-to-relocate-from-russia-2022-7-21-0/

[21] See the very-pleased-with-itself US Centcom report here: https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/NEWS-ARTICLES/News-Article-View/Article/3123432/regional-cooperation-2022-military-exercise-begins-in-dushanbe/

[22] The discussion here focuses mainly on US-promoted sanctions, but the UK and EU countries are also quite fond of sanctions on their own account. The EU sanctions regime is outlined here: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/eu-and-world/sanctions-restrictive-measures/overview-sanctions-and-related-tools_en

[23] A key example of recent years was when Chinese 4G and 5G telecoms equipment was branded a ‘security risk’ by the US in its bid to destroy China’s Huawei technology company.

[24] Note that when one company has to pay another for goods received, it does not normally do so by cash, but by bank transfer to that company’s account. So the bank plays a key part in settling the transaction. When the payment goes outside the national bank network, SWIFT is the most commonly used message system to direct it to the correct destination.

[25] By comparison, the BIS global survey for 2019 showed the euro – the currency of 19 European countries – was involved in only 32% of all FX deals. Despite China being the world’s biggest trading country, China’s renminbi made up only 4%, reflecting how most goods are priced in terms of US dollars, as well as the bulk of transactions being financial, outside of commercial trade. Note that the total shares of all currencies add to 200% because there are two currencies involved in a single transaction.

[26] See https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/office-of-foreign-assets-control-sanctions-programs-and-information

[27] https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-central-bank-will-not-name-banks-linked-swift-alternative-2022-04-19/

[30] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/india-introduces-mechanism-for-international-trade-settlements-in-rupees/articleshow/92806691.cms?from=mdr

[31] https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2021/06/28/indonesia-china-to-reduce-us-dollar-in-bilateral-trade.html

[33] https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-considers-accepting-yuan-instead-of-dollars-for-chinese-oil-sales-11647351541

[34] See https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/81357/. For a recent report on Turkey and Russia, see: https://www.rt.com/business/560359-turkey-unveils-russia-trade-plans/ and on Iran, plus other information on Mir: https://thecradle.co/Article/news/14395.

[35] The SDR components are 88% from Western currencies; with 43% US dollars, 29% euros and close to 7.5% each for the Japanese yen and UK pound. China’s renminbi accounts for 12%. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2022/07/29/pr22281-press-release-imf-determines-new-currency-amounts-for-the-sdr-valuation-basket

[36] ‘Russia moves away from “toxic” dollar and euro in economic relations with partners’, 20 August 2022, https://tass.com/politics/1496159.

[37] Data in the next chart are from annual reports of Russia’s central bank, with the latest available data for end-2021. ‘Other FX’ were likely all to be other Western currencies, including Japanese yen. The figures for stolen FX reserves do not include the private assets of Russian citizens (‘oligarchs’) or corporate assets seized illegally by Western governments.

[39] Most central banks hold a large proportion of US dollars in their FX reserves, reflecting its importance in global trade and investment, although that share has been falling slowly. China’s share of dollars has not officially been published since 2016, when it was 59%. It is now likely to be less than 50%, compared to a global average of just under 60% for countries reporting their allocations to the IMF. Although it is a more visible sign of the US dollar’s influence, central bank dollar holdings are only a minor part of its pervasive role in global finance.

[40] Hong Kong is obviously part of China, but its economic data is counted separately in statistical reports. Hong Kong’s financial system is also run separately from that in mainland China.